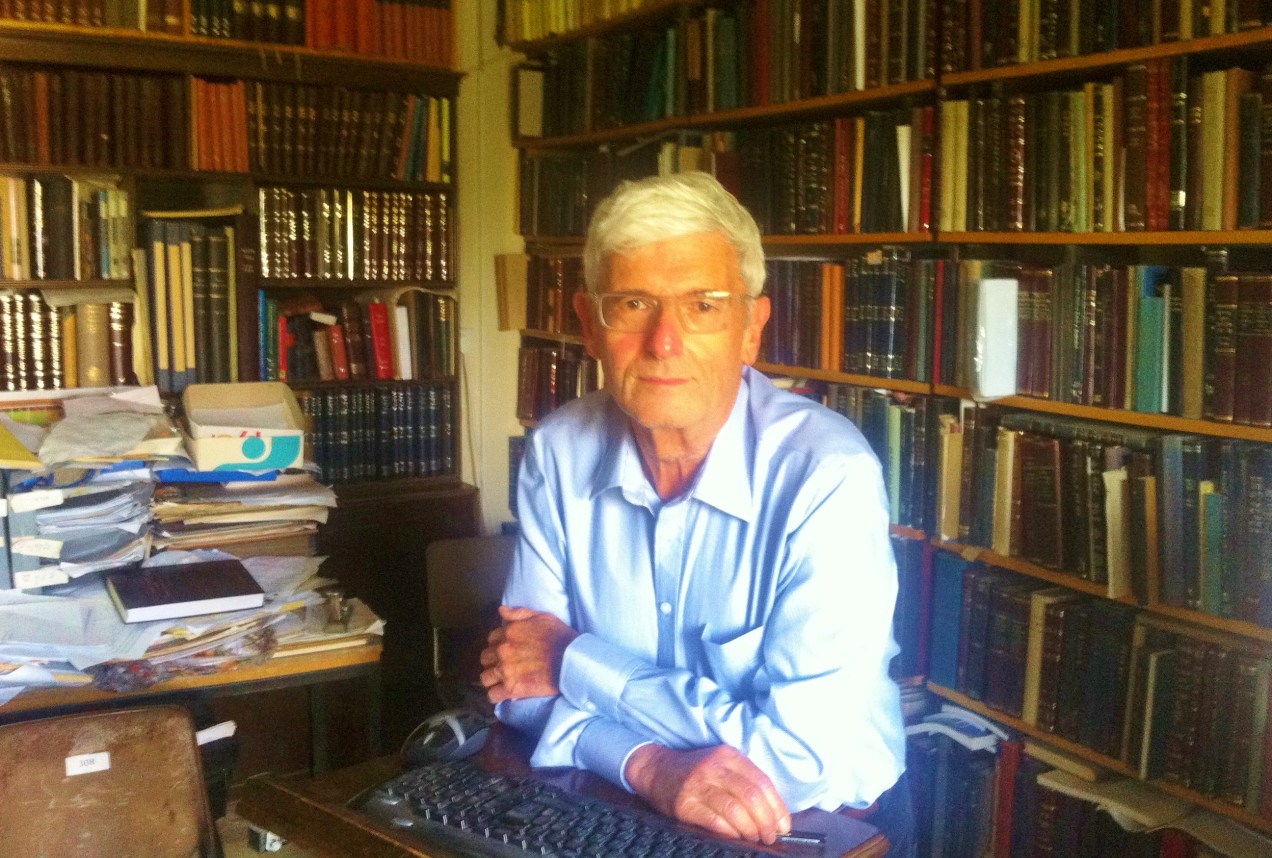

Today, May 6th 2014, Prof. Shamma Friedman of the Jewish Theological Seminary and Bar-Ilan University will be awarded the Israel Prize in Talmud, the most prestigious prize that the field has to offer. Over the course of my undergraduate studies at Hebrew University, I had the great fortune to work for Prof. Friedman as a research assistant. Earlier this week I visited him at his office at Machon Schechter to conduct this interview, and to continue work on his new website.

Friedman’s office is a place of pilgrimage for students, scholars, and just about anyone interested in the academic study of Talmud. I have been amazed by the amount of time Friedman generously gives to all who seek his counsel, whether they be established scholars like Prof. Haym Soloveitchik, administrators from the seminary like Chancellor Arnold Eisen, an interested layman, or a young yeshiva student bitten by the academic Talmud bug. Friedman seems happy to speak to anyone with whom he can share his excitement for Talmud.

Several months ago, before receiving the call from MK Shai Peron, Friedman was in and out the hospital with a health issue. He had an amazingly quick recovery, and managed to read countless articles and books while home-bound. On his first day back in the office at Schechter, he was accompanied by his wife, Rachel, who was concerned for his wellbeing. Rachel informed me that the doctors had told her husband that he could return to his normal schedule. They may have thought otherwise had they known that a “normal schedule” for the 77-year old Shamma Friedman means being at his office six days a week, standing at his shtender in front of his computer screen for hours on end. Amidst countless shelves and piles of books, with classical music from “Kol Yisrael” playing in the background, Friedman only breaks to speak to visitors and to teach his weekly class. His insatiable curiosity drives him to read yet another line of Talmud, to check another manuscript of the Aruch, to run another search in the Lieberman Talmud Text Databank — his face lighting up with every new discovery. Given the centrality for Friedman of his “home away from home,” it is fitting, as Rachel insisted, that part of the photo-shoot for the Israel Prize be done at the office. And it never occurred to me that I could interview him anywhere else.

YL: Prof. Friedman, for more than forty years now the focus of your research has been the Bavli. How did that happen? Your first book and PhD dealt with the medieval commentator R. Yehonatan of Lunel.

SF: I have been asked questions like this recently in one form or another and I don’t really have a good answer, or at least not an exciting answer. I never sat down and decided what I have to do, or what I want to do, weighed the possibilities and came to a decision. Actually, in most of the academic decisions I made over a long period of time I was really quite passive. Things just happened. Strangely passive in retrospect, especially given that one might say wait a minute, these are important things! A certain amount of siyata deshmaya, min hashmayim, yad hagoral, mazal, or whatever, played much more of a role than my making a clear, objective and weighted decision at any point.

I did not know that I was doing a PhD until I was told that I was doing one. I did not know what my research would be until I was told. “Told” in the sense of “helped.” I did not know what I would work on in my PhD until it happened. Before you ask me how I got to the Bavli, you should go back and ask me the simple question — why did I go to the Seminary?

YL: Why did you go to the Seminary?

SF: Well, definitely not because I wanted to work in the pulpit rabbinate. What I wanted to do was to learn and study in these fields and the Seminary was an excellent place to do it. I didn’t fight the fact that if you go to the Seminary, you came out as a communal rabbi, but that definitely was not what I was after. I was after the studying itself — I enjoyed it, I was attracted by it. And during the course of my time there the Seminary came to the decision that they would create what was then called the “Talmud program”: a concentration in Talmud study that freed you from other types of coursework, most certainly practical rabbinics, as well as other things too. It was mainly, Talmud, Tanakh and history — that was about it. More of a graduate program in that sense. And behind the Seminary’s decision to found that program — you see, they’re the one making the decisions — was a realization that the Seminary needed to train the future generation of faculty. At that point, just about the entire faculty was European-trained — where will the others come from? They established a PhD program, there was a modest stipend, we had a meeting in the sukkah in which Lieberman announced this program, and to me it was very good — I was happy to go along.

And so, that decision was made for me. Lieberman assigned to me Peirush R. Yehonatan of Lunel to Bava Qamma, and he assigned me to Dimitrovsky, who was also my teacher at that time and who was a wonderful guide. My head was completely in editing R. Yehonatan’s commentary for four years. I didn’t think about what I was going to do afterwards. I never made a calculated step to move into an academic career either. That was also a decision that was made for me when I was appointed to teach at the seminary, and I’ve been there since. A type of inertia. So after I got my head out of four years of R. Yehonatan, I came across certain things that I read agav orha, along the way. Somebody shared some offprints with me and I read Hayim Klein, I read Heschel’s Torah min haShamayim, I eventually got to Avraham Weiss. Especially by reading Hayim Klein — that’s where the change in my thinking took place. I started to see the daf of gemara differently. I was also taken by Louis Jacobs’ concept of the Bavli’s literary conceit, and Avraham Weiss’ work on literary forms such as the sugya, memra, kovetz.

YL: Weiss also talks about the development of the sugya and of the Bavli, what he calls “shikhlul.” Did that have an impact on you at all?

SF: Yes, on the deep level, Weiss had the idea of intervention, or editing of texts — I think you put your finger on the right thing — that’s an idea that’s also quite clear in Klein, and not necessarily part of the regnant line of thinking of the time, according to which “yesh masoret, ki yesh masoret lifnei khen,” and a certain belief in non-intervention. Weiss did show that there actually is quite a lot of intervention going on in the Bavli.

But even after reading Klein and Weiss I didn’t sit down and say, “I’m going to work on sugyot or the structure of sugyot.” That’s something that really came out of teaching. I decided to teach the tenth chapter of Yevamot, haIsha Rabbah, because I was interested in a specific sugya there, in the idea of “beit din matnin la’aqor davar min haTorah.” It’s somewhat ironic to me that I was first led by an idea and not by a text, given that I often terrorize my students by telling them not to go by svarot, and that first we deal with the text and then we deal with the svarot. I wasn’t really satisfied with how we finished up studying the perek, particularly the first sugya,so I decided I’d teach the perek again the next year. And then I figured out what happened there in the first sugya, and I said, “I’m going to write an article on this sugya.” However, by the time I got to the second sugya, the same thing happened, and I said that I would write an article on the second sugya as well. I didn’t think “now I’m starting Talmud haIgud,” yet when I got to the third sugya I did realize that I would have to write on the entire perek. From that emerged the concept of the genre of writing consecutive studies of parshanaut, commentary, of Bavli. And, well, hitgalgel davar li-tokh davar.

YL: What about nusach, real manuscript work, which isn’t really there in your commentary on haIsha Rabbah, but features heavily in your work after that. How did you end up writing such detailed work on Bavli manuscripts?

SF: Did I study textual theory? Did I even decide that this was what I was going to do? Absolutely not. All I was doing was teaching haSokher et haOmanim — which after I published haIsha Rabbah, became the target for really doing-up a perek — to a group here in Jerusalem. One of the people who welcomed me when I came on Aliyah, and who was interested in the scholarly work I was doing — and don’t forget that it was 1973, so a lot of these things weren’t out there yet — was Shaul Stampfer. Shaul actually got me to talk to a little group about what I was doing. And then Shaul said, “okay let’s set up a shiur.” He had an excellent core group who today are excellent professors in various fields — Chaim Milikowsky, Baruch Schwartz, Peretz Segal, Shaul, at some point David Golinkin. The group ran undisturbed for five years in which we studied haSocher et haOmanim and haSokher et haPoalim — fifty sugyot, and then I had to decide: do I see myself as a person that writes, or do I see myself as a person who primarily teaches? And I wanted to write it, I had all these ideas that came up and I wanted to write. So I told the group that I no longer had the time to continue preparing new material.

About that time I had a year at the Institute for Advanced Studies, which was actually the institute’s first year, which was located in the Truman building up on the Mt. Scopus campus of The Hebrew University of Jerusalem. The central scholars were Lieberman and Scholem, and each of them, in addition to having a double office, was allowed to bring on two younger scholars, so Lieberman brought me and Danny Sperber. It was rather odd that they put us up on Mt. Scopus in the Truman building. We were supposed to spend the whole day there, but there were no books there, and of course, no internet. So there was a research assistant who would go to the National Library and bring us whatever we would want. The assistant was Yehoshua Schwartz, now a professor at Bar-Ilan. I didn’t ask to be in this group, and I said that it was purely min hashamayim,and I didn’t ask to have a research assistant, so I said “what do I with a research assistant?” I told Yeshoshua to get me copies of all the manuscripts of haSokher. So he photographed all of them, and I was able by then to incorporate the girsaot into what I was doing, and it hit me one day, and I still have that piece of paper, it hit me that the Florence and Munich manuscripts in that chapter are a team, that they represent a tradition — a little later it would turn out that there was a counter-tradition, represented by Genizah-Hamburg — but when I saw that they have a tendency to go together, I wrote on top of the piece of paper, that I still have, “Rosencrantz and Guildenstern,” whom always appear together in Hamlet. I’m telling you this just to show how devoid I was of all of the talk of stemma, and so forth. It’s just that ha-dvarim histadru li-neged einai. I was an observer, hayiti mashqif min ha-tsad, min ha-hutz. I looked at it, and I saw things.

All the other areas that I worked on — language, tannaim, and the other studies — were by and large offshoots of the consecutive treatment of texts of Bavli, of sugyot, which led me to the great value of this method, in contrast to picking specific topics. The discipline of consecutive text, which I began with, leads you to things you wouldn’t have otherwise gotten to. If you’re looking at things with a hard look, you don’t walk around them, you’re forced to address them, and ultimately, that can lead to interesting investigations.

So with the correct fact that you began with, that the Bavli is the very central center piece of what I’m trying to do, my hand is at the same time in all these kinds of offshoots, like language. For instance, Matthew Morgenstern bases a lot on my work in articles like “Shayarei kitvei-yad.” Here’s what he writes in his recent book on Jewish Babylonian Aramaic [Studies in Jewish Babylonian Aramaic, pp. 33-35 — Y.L.]:

The most significant publication of the early 1980s was a seminal article by Friedman, “Early Manuscripts,” which has unfortunately escaped the attention of many Aramaists. While undertaking a study of early manuscript sources for the Babylonian Talmud tractate Bava Mezia, Friedman reconstructed from fragments found in several libraries the remains of a substantial Geniza manuscript, which contained virtually all of the sixth chapter of the tractate, as well as parts of the seventh chapter…The significance of this manuscript lies not only in the fact that it contains an early version of the textual tradition…, but also that its language is of a type that until then was known primarily from Geonic manuscripts. Friedman effectively demonstrated that many of the characteristics associated with the best Geonic sources (plene orthography, phonetic spellings) also appear in early Talmudic manuscripts. Hence the manuscript’s textual status (early eastern) rather than its genre/provenance (Geonic) determines the nature of the language (p. 24).

YL: Interestingly, Lieberman did not actually write that much about the Bavli, even if he taught it at the Seminary. How did he perceive of your work on the Bavli?

SF: I have some fantastic material on that, but since they were so personal, I never really promulgated it. In a letter that he sent me he makes a general statement that the methodology I use is correct:

שמא יקירי, רק היום הספקתי לקרוא את מאמרך “קידושין במלוה” ועלי לאמר שהיתה לי הפתעה מאד נעימה.

הנך צודק כמעט בכל דבריך, ושיטת הניתוח היא אמיתית ומדעית עד לאחת.

לרגלי עבודתי אין בידי לעמוד על כל סוגיא וסוגיא ולקיים בה הדמין תתעבד, ובאים תלמידיי וממלאים את החסרון.

תתברך מן השמים ליישר כחך לאורייתא

באהבה

שאול ליברמן

With the help of God, Thursday of the week of “Remember what Amalek did unto thee” 5735

My dear Shamma,

Only today did I have time to read your article “Qiddushin bi-Malveh” and I must say that I was most pleasantly surprised. You are correct in almost everything that you wrote, and the method of analysis is both accurate and scientific to the utmost point. Due to the intensity of my current work, I cannot address each and every sugya and fulfill ye shall be cut into pieces [see Daniel 2:5 — Y.L.], and my students come and fill in the gaps. You should be blessed from the heavens and may your strength be directed towards the Torah.

With love,

Saul Lieberman

From Prof. Shamma Friedman’s personal collection.

I later found out that he always uses the word “kimat,” when I saw that he also used it in a letter to Sperber that Sperber published. The article he’s referring to in the letter to me was a very early article — “Qidushin bi-Malveh” [published in Sinai 76 — Y.L.], in which I even disagreed with something that Lieberman wrote in his Tosefta, and I said that “וכבר לימדונו רבותינו כמה פעמים, שאין לדיין אלא מה שעיניו רואות” — which is something that Lieberman always said. Lieberman certainly would have known that that was essentially a “nitilat rishut”, and he was extremely positive about that article.

And there’s a passage in Tosefta ki-Pshuta in Bava Batra where he refers to me as his “talmid muvhak.” Why is he quoting me? I once asked him a question while I was working on haMafkid — does the word “nifkad” ever appear in the Yerushalmi? I had to ask Lieberman because I had already reached my conclusion, but I didn’t have a concordance for the Yerushalmi, so therefore I had to ask him. He liked the question, and he said “no,” and then when he touched that point while doing Tosefta Bava Batra he quoted me as making that point.

YL: You mentioned that there is a difference between your commentary to the tenth chapter of Yevamot and your commentary on haSokher et haOmanim in terms of the work with textual versions. Has anything changed in your methodology over the years?

SF: As you know, the major evolution occurred mostly towards the beginning of my career while working on haIsha Rabbah, and that that came out of teaching. Already in the introduction to haIsha Rabbah, which I wrote while I was already working on Bava Metsia, I say that in the work on Bava Metsia I will give a full representation of the sugya. I don’t give the full text in Yevamot, and the use of girsaot is only agav orha to see the best way to say a word — it’s not heker hanusah. I should also note that when I started working on Yevamot I really had something else in mind. The original topic was to be the structure of sugyot and structural patterns within the Bavli, and it was the experience of trying to understand the sugya that switched me from dealing with structural patterns to parshanut, because I became more fascinated with understanding the languages or the texts of the Bavli, which of course created all sorts of problems.

I think that the reader of haSokher has the sense that the commentary is too long — it goes into too many things. In my language, it’s “too perfectionist.” I thought that we could write a Tosefta ki-Pshuta kind of commentary on the Bavli, even if the obvious differences are clear: the Bavli is different from the Tosefta, and the writer is different from Lieberman. For both of these reasons it could maybe be on one perek or on several, but not more. The nature of what Lieberman does on just every line is just so overwhelming, and that sort of became a pattern of what I strived for.

One of the things that most impressed me while working for Friedman is his curiosity, which, combined with his thoroughness, can be somewhat of nightmare for a research assistant. Friedman must see the German original of a hard-to-find article by Gustaf Dalman; he must then get a copy of the pages from the work of another Lutheran Orientalist referenced by Dalman, only to then send his research assistant back to the library to locate that author’s doctorate. “What you photocopied for me really whet my appetite.”

All of this is on display in his footnotes. Friedman writes for someone like himself. Someone who would want to see the full quote both in its official English translation and in the original German along with a brief biographical sketch of the scholar at hand, and someone who, even though he may well have much of the material on the shelves of his personal library, would prefer not to be mivatel Torah for the few minutes it would take to retrieve the volumes, because hamelakha merubah…

An example of Friedman’s footnotes: footnote 17 in his article “On the Origin of Textual Variants in the Babylonian Talmud”.

YL: Besides the editing of the text and style of commentary — what else has changed, even since haSokher?

SF: Earlier I was talking about separation with the aim of scrutinizing the memrot, and not so much scrutinizing the stamma. The switch that took place more recently with my article “Al Titmah” [published in the volume of essays Malekhet Makhshevet and in Friedman’s Sugyot — Y.L.] is that I began to look at the stamma as a fantastic corpus within itself, and therefore the stamma doesn’t simply have to be shaved off in order to get to the memra.

Another shift was a much a greater emphasis on the tannaitic world, and this also came about over the course of sugya by sugya work in haSokher — particularly in the ninth sugya, nefah umasui [in the Commentary, pp. 223-238 — Y.L.]. In that sugya, unless you put together the Tosefta, Baraiyta, and Mishnah, you can’t understand what’s happening in the Bavli or in the sugya, and that reflected itself in the whole subject of Mishnah and Tosefta. That’s one of the formative parts of my thinking, and it’s so complex that I’ve never really repeated it in any of my more methodological studies — I usually just said in two or three words, “see there.” But this was really formative, the Mishnah and Tosefta thing. Also the toseftan Baraiytot study in the Dimitrovsky volume came out of the sugya by sugya work.

An additional aspect of the adding of more emphasis on the tannaitic side will be seen in my commentary to the ninth perek of Gittin. In haSokher there’s a strange thing — the Mishnah doesn’t even appear! I deal with the sugya, and I refer people to the Mishnah, but I didn’t deal with it myself. In Gittin, I don’t deal with every Mishnah, but in many cases there’s a special unit for the Mishnah because there are things to say about it that I can’t simply say to the reader, “learn the Mishnah and come back here and we’ll do the sugya.”

YL: How about the attempt to recover the original memrot — has anything changed in that regard?

SF: I’m reading a book about physics now. It’s really a fascinating book, I don’t know if you’ve heard of it, it’s by someone named Zvi Schreiber, and it’s called Fizz, and it’s about a girl named Fizz who time travels and visits all of the great physicists from Aristotle, Copernicus and so on. The type of thing that happened to me happens in the History of Science: once you find something or understand something, and based on your understanding that you’ve picked up, you can kind of do an about-face and change the basis that the understanding was based on. What it means in this case is like this: there are memrot, there is stam hatalmud, each one is very clear; you can see the memrot in their literary form, we have parallels in the Yerushalmi; you know the language and we know what the stam hagemara says and how it talks and how it fills in space betweenn memrot. I say this in “Al Titmah”: having gotten to a sense of the style and touch of stam hatalmud, we now confront things that look like memrot but sound like stam hatalmud. I find a sufficient number of cases like this, including that very interesting case in Ketubot about 32b-33b on which I had a long discussion with Robert Brody [Sugyot, pp. 105-109 — Y.L.]. I’ve been seeing a lot of this in Gittin, and that will come through in the volume. The mahloqet of Abaye and Rava about “al mnat shelo tokhli basar hazir” [b. Gittin 84 — Y.L.] — I can’t see Abaye! It has the scholastic feel and the rhetoric of stam hatalmud, and therefore I conclude that it is stam hatalmud using Abaye. While I was writing “Al Titmah,” I didn’t realize how this was such a central part of my thinking.

The stam hatalmud uses Rav Papa’s and Abaye and Rava just like it used R. Yohanan to display Palestinian material. This will be a “pizmon hozer” in the Gittin volume, and it comes up a lot in my volume “מונח מונח רביעה” which discusses four munahim, each one taking up a reva of the book.

These methodologies of the study of the Bavli of the recent decades are sort of a “torat hasod” that’s known only by the inner circle, and people in related fields are often using methodologies that are a hundred years old when they get to the Bavli. To be sure, there are people like Menahem Kister, a talmudist whose work in recent years has focused on adjacent areas of scholarship, that have sophistication in all the fields, as can be seen in his fantastic recent article on Metatron [Tarbiz 82 — Y.L.]. But people farther out, in different fields, never had a chance to get these insights, and therefore you can overturn a lot of what they say. One of the frustrations that I have in talking about these two books of mine, Gittin and Minuah, is that they really represent my thinking of the last ten years, which is not even available to the inner circle! I use an article of mine on magic that is due to come out soon in English as a way of introducing the uninitiated into the methodology, and there’s a great example of how separating the layers and really understanding the sugya helps us make sense of the theological issues. Essentially, the nature of magic is generalized from stam hatalmud, whereas there’s a basic mahloqet amoraim about whether it’s real or not [the article has since appeared in Rabbinic Traditions between Palestine and Babylonia– Y.L.].

In 1973, after having already been an assistant professor at JTS for six years, Friedman and his family moved to Israel. From then and until 1990 Friedman directed the Seminary’s Jerusalem campus at Neve Shechter.

YL: Why did you and Rachel decide to move to Israel?

SF: We wanted to, we loved Israel, we loved the language, we had been thinking about doing so for many years. In 70’-71’ I spent a sabbatical here and the kids were already in schools and had friends. The trick wasn’t coming, the trick was doing so and still staying within the Seminary. That was a trick that I had enough hutzpah to try. Most of the things I’ve done with scholarship take a lot of hutzpah, but I assure you that it’s a lot of naïve hutzpah. In those days people were frozen into non-action because of Lieberman. You couldn’t operate in the field when there was something like that. I didn’t see myself as competing with Lieberman or something like that. In the talk that I gave over at his shloshim I told the story that Lieberman used to call on people to read and he would say “read now…” And then there was a pause in which he would think of who to call on and everybody was terrorized. Everyone would look down and avoid eye-contact, and I used to look him straight in the eyes. I don’t know how I had the hutzpah to do something like that. It was a pause of many long seconds that I used to look him straight in the eyes, and he wouldn’t call on me, because he knew that I wasn’t afraid to read. But the same thing went with my writing. I wrote that article disagreeing with Lieberman in Sinai, and it took a lot of hutzpah.

People tend to discuss Friedman’s work alongside that of another Israel Prize Laureate, Prof. David Weiss-Halivni, in that around the same time, both began to publish scholarship that broke up the sugya into different parts with emphasis given to an anonymous redactional layer. While multiple differences between their approaches have been noted, one of the stark differences in their output is that Friedman has not published a theory of how the Bavli came into being, whereas Halivni has.

YL: According to Rav Sherira Gaon, Rav got to Bavel in around 219. Then what happened?

SF: several people have dealt recently with the ambivalence of the Rambam to the Geonim and how behind his apparent admiration for them he doesn’t simply accept all of what they said. Haym Soloveitchik explained to us that the mindset of the Arabic speaking Geonim was somewhat of a shift from the Talmudic thinking, and certainly there are parts of Geonic writings that have a simplistic way of explaining the gemara and tend to explain things literally. Isaiah Gafni has already written on this in regards to Rav Sherira. So, Sherira Gaon says that Rav brought the Mishnah from Eretz Yisrael — it’s a little too simple. I have not worked on this issue per se, but it’s too clean and absolute of a kind of thing. One thing that I have touched upon is the concept of mishnat bavel and mishnat eretz yisrael, which Y.N. Epstein formulated in his lecture at the opening of Hebrew University in the twenties. I think mishnat eretz yisrael is quite clear, but you can’t really find mishnat bavel and therefore it’s one of these absolutes that must be dismantled. But as per your question, how exactly did the Bavli come into being from the first generation of amoraim — I don’t have a lecture on that. I guess I have some ideas, but, per se, I’m working on the memrot, and not on the translation to the historical examination.

YL: If I may, it seems like you see yourself more as a commentator than as someone who would write an historical introduction.

SF: Right, of course. Well, I have big introductions to everything, but they’re methodological. I’m interested in methodology. But my hero is the Rashbam — omek hapshat, pshatot ha-mithadshim bi-kol yom. If you bore down far enough you’ll get to the real pshat, or as close to the real pshat as you’re going to get.

YL: Who are you favorite Rishonim or Ahronim, or who are the ones that you commonly use?

SF: Well look, with Rishonim, I’m so involved with Rashi and Rambam. I’ve written a lot about that and I think that when the Rambam went up to yeshiva shel ma’alah, he went and visited Rashi right away. I have another unpublished Rambam article that I’m working on, and I have a lot of notes where I quote Isadore Twersky in about seven or eight places in which he says in very simple language: the Rambam was not a modest person. He actually says that –the great Twerksy! Of course, he says it nicely.

What I’m often impressed with is the tremendous genius of Rashi, combined with his modesty. I still am fantastically excited by reading Rashi. We must allow our eyes to sparkle a little more when reading Rashi. Avraham Grossman shows you how to do that in the certain issues that he has dealt with — Rashi’s attitude towards women, for example, as well as other things. But there’s a tremendous amount in Rashi.

In terms of Ahronim: you know that ani lo ish Ahronim — but I have picked up from what Lieberman said and I think it’s quite correct. There are certain Ahronim or certain schools of them that have the roots of the critical philological approach — in contrast to others with other approaches — and one of them is the Ohr Sameach.

YL: How do you see academic Talmud and your own scholarship fitting into the larger history of Jewish learning?

SF: You know the story about somebody that comes to some gadol, rosh yeshiva, somewhere in Jerusalem, and sees that Lieberman’s Tosefta is there. So he says, don’t people ask you why do you have Lieberman’s Tosefta? So he says: look, people who don’t know what it is, don’t ask me, and people who do know what it is, certainly don’t ask me! We find tremendous excitement in Wissenchaft, in madaei hayahudut, in Lieberman and Epstein. It’s so exciting that your first sense is that if you show it to people then everybody will want to use it! Look, that’s true to a certain extent, but we have to be realistic — and in terms of sociology, there’s too much ideology in certain sectors not to look at these things. We won’t get to the vort. It won’t happen in our time — but the scene is so variegated that it will reach a lot. I mean on the dati scene, take places like Ma’ale Gilboa or other yeshivot, where they are incorporating our work.

YL: Do you see academic Talmudists actively trying to make it into the larger world of Talmud study?

SF: It has definitely come up in some recent thinking of Talmud haIgud– –this idea of communicating the exciting aspects of philology and other research methodologies to people who learn in the more regular way, the way that it used to be in the earlier decades. We don’t say that this is the Igud’s goals. We’re going to have Talmud haIgud — I don’t know why exactly. It’s like everything else, because we want to understand the gemara! Because we wanted people to apply our approaches, to analyze sugyot, so that when I learn that perek I can benefit from their scholarship. Let me show you a reaction that I got from someone:

[Talmud HaIgud gives] the serious, open minded Talmud scholar, as not yet aware of the beauty and power of the academic approach, an opportunity to get hooked. How many superlatives can I use to describe the latest addition [=Benovitz]. Amazing! Fantastic! The best part is that he addresses all the issues that bother me and finds great answers. Regarding Wald, here is a very brief assessment. His definitions of the key concepts in Shabbos in the introduction are superb. They go beyond the standard definitions in their scope and relationship to each other. His grasp of the material is especially evident in Sugya 16, Hunting the Chilozon, where his explanation of Peshik Raisha D’Lo Necha leh in the context of this sugya is the best I have seen.

Here’s a quote from someone who reads our work who isn’t from the world of academic Talmud, Dr. Shalom Kelman of Baltimore, a physician and a very competent talmid chacham. He’s very fast — he can dance around me in terms of speed — he introduced himself to me and he’s always full of enthusiasm. And there are many other such people that we reach as well.

YL: You insist that you’ve been passive all along, but it definitely does seem like you have a vision.

SF: Yes, now I do! There’s no question about it, and the projects were essentially tools in order to do this — tools that I wanted. I wouldn’t say I made the bibliography for other people to use, but ner li-ehad ner li-meah.

YL: What do you think of where the field is now?

SF: I’m very impressed with the field, people who I consider younger but are really already accomplished professors already. I see myself as part of a generation that was a sort of a bridge generation. Here we had on one side giants — Lieberman — and now we have on the other side people who are very capable, but who are coming from a different world. Reading Kister’s article now is one example, maybe he’s a more outstanding one, but there are really many very capable people that are writing today and in a sense they’re much more disciplined, they have better backgrounds and training, they do the language side carefully, etc. I see so much talent and exciting work that’s coming out of people not yet retired and even from people who are just finishing their doctorates. People who are well versed in all kinds of different fields, which is not easy today considering how much is out there. There are good things happening.

YL: And how about even younger — how do you think that Talmud should be taught in High Schools in Israel?

SF: I don’t know if you know — during the Yom Kippur war I volunteered to teach in LiYadah [Hebrew University’s High School — Y.L.]. That was a time when they were studying Talmud, so all you had to do was be a substitute teacher and teach a little different. Now, I don’t even know how to get it back into the curriculum. I have these little ideas of Talmud education and I’ve discussed this before. What I guess is one of the reasons why Talmud has a bad name that would have to be overcome — this goes back to a talk that I gave at a conference for mamlakhti dati Talmud teachers and principals in the late seventies or something like that, which I mentioned in my Chair talk. I think that if a teacher is strongly intellectually engaged in the material he’s going to communicate, then the way to do it is to prepare himself for his own needs before preparing his lesson. And then I started preparing a list of things that he would need to prepare and they laughed me out, because I was essentially describing how I would prepare for that group that Shaul Stampfer put together that I told you about before. So I gave that sort of recipe of those seven things, structure of the sugya, and the relationship of the component parts, and the influence of the stam hatalmud. What I did in LiYadah was simply the idea of undressing the sugya first and then reattach the stam hatalmud. So I took out the memrot, and the divrei tannaim, and I said okay this is what this says and this is what this says, all of which makes sense. Now let’s see how the Talmud integrated that into discussion, which immediately gives a double way of approaching what the memra says itself and what the stam hatalmud creatively had to do, even though it wasn’t the “pshat,” in order to weave the things together. Now the students are not shocked by the strangeness of the Talmud — are the memrot or beraiytot strange? No. Is what the stam hatalmud wanted to do strange? It’s creative, but it’s not strange. You can begin to understand what someone would like to do, which is quite different from if you teach it monolithically.

As anyone who has visited his office knows, Friedman has collected quite a few books over the years, some of which are placed on rather high shelves. On one occasion, while his arm was in a sling due to a fall, Friedman asked me to return a rather heavy book to a rather high shelf. After climbing up on a chair and lifting up the book, I had to ask him: how did he get the book down in the first place? “The man I am when I want a book isn’t the same man that I am when I need to put a book back.” The delight in whatever sugya he is learning that gives Prof. Friedman so much energy, as well as pleasure and excitement, continues unabated.

SF: I’ll give you an example from something I’m teaching right now from haHovel. Every sugya I teach I always think “this is the most fantastic sugya.” Some of the things in the Talmud are funny, there’s humor, there’s exciting things, there’s things that make you jump, but there’s different genres within it, and one of them are piskei halakha, as Rashi says, and the piskei halakha that we have here are in the form of a list of arguments that the hovel can make to the nehbal, and all of the answers are all pitgamim. After you break your head on a long and interesting sugya with a complicated mahloqet — don’t skip over the beauty of those last four lines, which although simple, are actually very exciting.

Yitz,

Many, many thanks!

YM

Nice job, Yitz!

Prof. Friedman – nice surprise to hear you’re reading my book Fizz!

Zvi Schreiber

Pingback: The Israel Prize 2014 « Menachem Mendel

What a fantastic interview. Yes, it’s long, but well worth reading to hear how he came to be a Talmud scholar and what keeps him going. I can’t wait to get ahold of his English article about magic in the Talmud.

Here it is Maggie- https://shammafriedman.files.wordpress.com/2014/06/now-you-see-it-now-you-dont.pdf