Perhaps more than other historical disciplines, art history is not merely auxiliary to art, it is integral. It can and has been argued that what renders a banal object a bona fide art-object is some conscious level of participation in the story of art. This is a deep truth about visuality – one which was once compellingly evoked in a scene about a time-traveling modern who baffled his nineteenth century friends with amateurish, minimalist etchings on frosted glass. And it is especially true of modern and contemporary art despite – or maybe because of – incessant attempts by provocateurs to try and blow up art history with one fell swoop of shocking red paint. When you vigorously oppose history’s centrality you only enhance it.

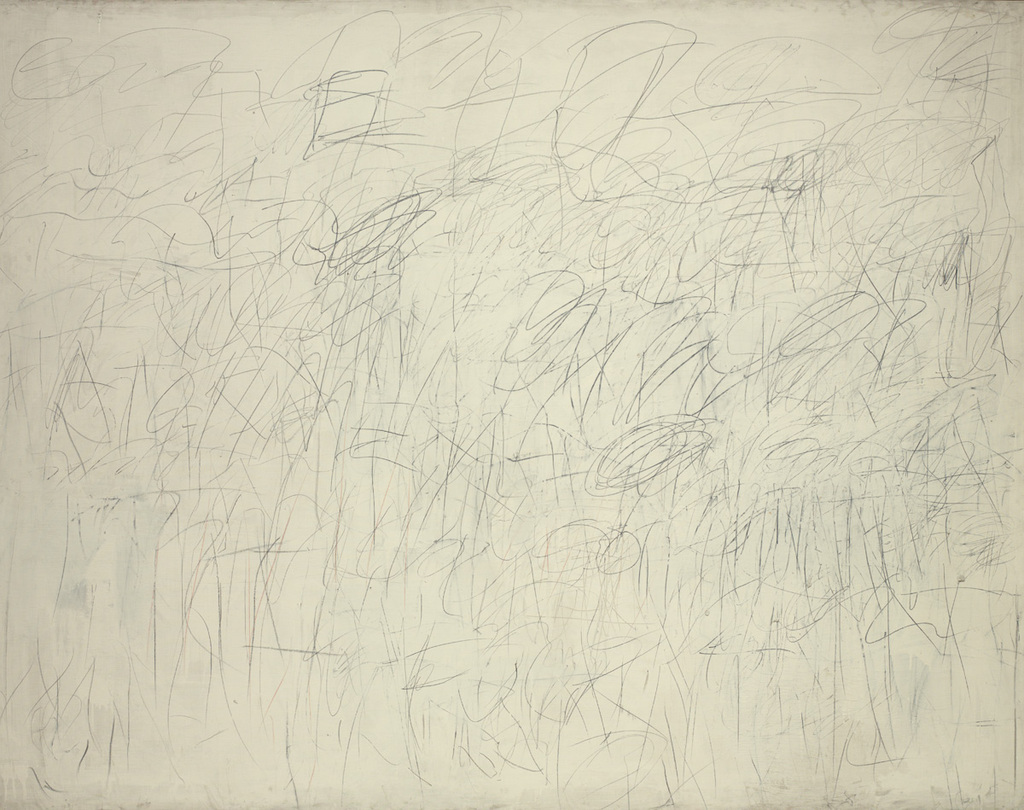

At New York City’s MOMA, the viewer snakes his way through the museum’s classic fifth and fourth floors and thereby traces a visual narrative with his feet and eyes. The curators have ever so carefully placed these famous galleries in their “correct” sequence with corresponding plaques on the wall so that the story coheres and the art properly resonates against its general historical milieu and its own art historical context. Without a previous “academy” to react to, Cy Twombly’s Academy is just vulgar scribbling (it of course remains that even after). One might say that herein lies the successful retort (teshuva nitzahat) to the everyday ‘heretics’ of modern art: Yes, you might technically be able to execute some of the chaos of contemporary art on your bedroom wall, but did you do it at the right moment, with the right intention, and with the right interviews and critics drawing out the greater significance of the project? Regardless, something is lost when art must always narcissistically fold into its own history. The pleasure of the thing, and perhaps even its essence, gets away.

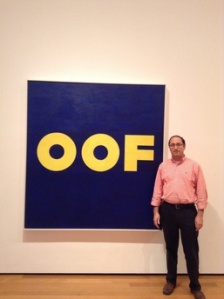

For some time now the dominant critical mode of studying the Babylonian Talmud has consisted of dissecting the sources on the page and placing them on a linear, chronological graph. The early tannaitic passage evolves into a later version, which is reinterpreted by early amoraim, reread by late amoraim, recast by editors, and reworked by redactors. Our mantra is a stutter: “re- re- re- re- re-“. If a Talmudist succeeds in unraveling this history and explaining its historical development – or better yet – correlating it to its historical context, the assumption is that he has succeeded in solving it. The thrill of this scholarly chase, its secret sleuthing and precious eureka moments, can be exhilarating, but also exhausting. What is left after the “problem” of a sugya’s development is “solved” other than to exhale Ruscha’s bright onomatopoeia?

This somewhat unfair characterization of the field need not be seen as a passionate lament, nor as a call to devolve into pre-scientific thinking (in any case, you cannot really go home again). It is instead offered as an honest, even hopeful question: Is this all there is? Or: What other critical modes might be combined with the currently dominant one to create a more complex – and hence truer – picture of the Talmud as something more than just the sum of its evolving parts?

First, we cannot forget that the growing research into the Bavli’s Sasanian context is still in its early years and will continue to yield succulent and novel insights, not all of it simply “more of the same.” There are new relevant sources that continue to come to light, and more importantly, new ways of correlating these sources to talmudic parallels. It is not all cut-and-dry Talmudic history. Readers of the Talmud blog also know that there already are other approaches out there that look beyond diachronology. These include the oft-maligned mishpat ivri school – especially as reinvigorated by Robert Cover, and also a group of literary approaches – particularly those focused on the text’s effect on its readers. In more hopeful moments I realize that where we are now is actually not such a bad place at all.

Pingback: Midrash Esther Rabbah | The Talmud Blog