Few texts present philologists with as many difficulties as the Babylonian Talmud, whose complicated transmission history – oral and written, spanning centuries and continents – has created countless conundrums that we are only now beginning to understand. At the same time, scholars dispute the proper way to understand the development of the text of the Bavli, meaning that opinions vary with regards to the proper way in which one should explain a difference in the Talmudic text: Is this event a consequence of fluidity during an early stage of oral transmission, or is it perhaps a later interpolation of a learned scribe? Such differences between textual witnesses of the Bavli are countless, and the different scholarly attempts to approach them are related to different ways of understanding how the Talmud developed over time. Thus, the close study of thousands of differences between manuscript versions of the Bavli not only helps explain the sugya at hand, but also sheds light on the development of the Bavli itself.

Despite the scholarly disagreements regarding how to properly assess textual differences – and by extension, the gradual evolution of the Bavli – there is certainly agreement as towards the main tools that should be used. Like most textual curators, philologists of the Bavli begin with cataloging: Compiling a list of all the textual witnesses to the section of the text in question. Since the publication of Y. Sussman’s Thesaurus of Talmudic Manuscripts, lists of the direct manuscript evidence are readily compilable. Similarly, Yisrael Dubitsky published an exhaustive list of early printed editions, hosted on the website of the Lieberman Institute (understandably, testimonia of the Bavli are endless, and it will take many years of work by individual scholars to amass the full body of such evidence).

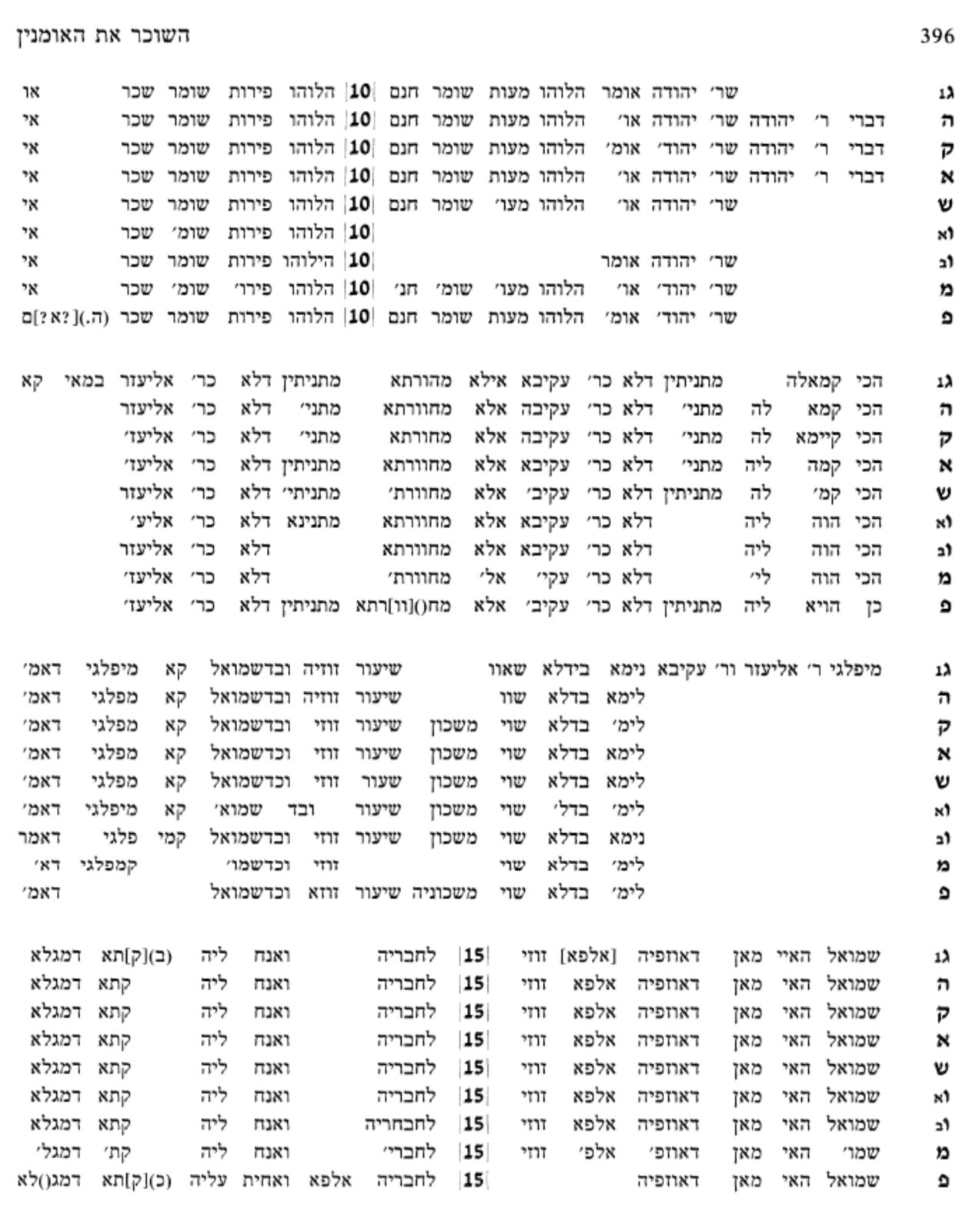

After transcribing the textual witnesses, it is widely agreed that the next stage, crucial in evaluating textual differences, is to collate the texts of the witnesses in what is commonly called a “partiture” synopsis – a way of presenting the text in which each version is layered over another word-for-word, creating a final product that is somewhat visually akin to sheet music. It is unclear to me when this practice first took hold in Talmudic scholarship. I do think it is clear that, beyond using such synopses as a means towards understanding the text better before commenting on it, more and more scholars now opt for leaving the text in such a state when they present “editions” of the Bavli. This practice reflects a growing consensus that an ur-text of the Bavli cannot be reconstructed, nor should a single, exemplary text be selected, and also out of the assumption that the ideal reader of such an edition would prefer to have the ability to wade through the large body of information on her own. If a “main-text” edition can be termed “diplomatic,” then we can term the synopsis “democratic.”

The virtues of the line-by-line synopsis are indeed numerous: All of the most relevant information is readily available to the editor or reader, the relations between witnesses are easily mapped, “outliers” and “contaminations” can be located, and more. Yet, transcribing all of the witnesses is a painstaking task, and the collation of the witnesses in a synopsis form is also time consuming. With a work as large as the Bavli, it has taken years for the field to produce only a few synopses of sparse selections of the work.

Enter Shamma Friedman. For decades, Friedman has been at the forefront of both talmudic philology qua philology (think dusty book filled offices, but also trips to pastoral European monasteries which are home to ancient Talmudic manuscripts) and digital research in the humanities. Since the eighties, Friedman has headed the Saul Lieberman Institute of Talmudic Research of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America. Friedman and his staff have poured thousands of hours into transcribing almost every single partial and complete manuscript of the Bavli. After years of being available on CD-ROM, the institute’s databank of Talmudic manuscripts went online in 2011 and has become one of the most relied upon tools for scholars of the Bavli. Now, in what will surely be remembered as a watershed moment in the history of talmudic philology, the institute has developed software that can automatically create synopsi. Using the software, synopses of a chapter of the Talmud can be created within the span of just a few minutes, and the day on which scholars will have synopses to the entire Bavli at their fingertips does not seem too far off.

For now, the Lieberman Institute is providing synopses “on order.” Scholars can request a synopsis of a particular chapter of the Bavli (based on the institute’s transcriptions) by emailing lieberman.index@gmail.com. For the moment, they have a preference for chapters from smaller tractates. The synopses appear in Excel documents, for the most part with each chapter in one document. Given that the number of columns in Excel documents is rather limited, some chapters are divided into more than one file (indeed, for that reason, Alex Tal has preferred to use horizontal synopses for his statistical analysis of manuscript relations of the Bavli). Besides the very ability to view a synopsis of whatever section of the Bavli that they like, the Excel format allows the scholar to manipulate the text in any which way: One can add additional versions, rearrange the manuscripts according to family resemblance, and correct the transcriptions according to their own reading of the manuscripts.

Friedman and the entire staff of the Lieberman Institute are to be commended for providing this tremendous service to the field. Now it’s up to the wider community of scholars to build off of their work.

Hey guys the plural of synopsis is synopses. Great article.

db

Jedenfalls aber ist unsere philologische Heimat die Erde; die Nation kann es nicht mehr sein.

(Our philological home is the earth. It can no longer be the nation.)

ERICH AUERBACH, *Philology and Weltliteratur *(1952)

On Sun, Feb 7, 2016 at 6:33 PM, The Talmud Blog wrote:

> Yitz Landes posted: “Few texts provide philologists with as many > difficulties as the Babylonian Talmud, whose complicated transmission > history – oral and written, spanning centuries and continents – has created > countless conundrums that we are only now beginning to understand” >

יישר כוחכם בברכה מרדכי

Reblogged this on Prof. Shamma Friedman.

Yasher Koach!!